|

The Kızılırmak is the artery which gives life to the

Anatolian steppe: to flowers, insects, people and the soil. With countless tributaries and

a length of 1355 kilometres the Kızılırmak is Turkeys longest river. It rises on

Mount Kızıldağ in the northeast of the central Anatolian region and is soon swelled by

a series of streams close to itself in size in its home province of Sivas. By the time it

crosses into the province of Kayseri it is already several times its original volume, and

continues to swallow up tributaries along its westward route past towns and cities. |

At Avanos the river swerves to

the northwest to pour into the Black Sea at Bafra. The Kızılırmak delta, with its

numerous lakes, large and small, is one of Turkeys most important areas for

birdlife.The Turkish name the Red River derives from the colour of the water,

whereas in antiquity the Kızılırmak was known as the Halys, a name meaning salty

river. This river valley was home to diverse civilisations over Turkeys long

history, and many traces of them are still to be seen today, such as rock tombs, castles,

bridges and settlements.

Five of us decided to follow the course of the Kızılırmak to see this ancient heritage

at close quarters along its valley created over thousands of years. We were to travel by

inflatable dinghy, and chose the month of June when the river water is at its clearest.

The first stage of our journey was that part of the river in the province of Kayseri,

where roads along its valley are virtually nonexistent and nature barely touched by man. |

This stretch of the river, approximately eighty kilometres in length, flows past no large

towns.Since differences in altitude are negligible in this part of Kayseri the river is

generally sluggish, sometimes appearing as still as a lake. But this tranquility turned

out to be deceptive, since on occasions we suddenly found ourselves racing along and being

swept over rapids as the river suddenly surged downwards. Our chosen method of travel

meant that we had to be prepared for accidental tumbles overboard and struggling to stay

afloat in the rushing water. |

|

|

The Kızılırmak valley frequently alters in

appearance with the changing geological structure of the terrain. Before reaching Felahiye

Bridge the river flows through high hills and occasionally rocky gorges, but beyond the

bridge this scenery makes way for volcanic rock. The river is here within range of the

eruptions of Mount Erciyes, the volcano which created this unique landscape. The colour of

the basalt rock constantly varies, particularly in the afternoon light, to spectacular

effect. The red hue of the river water is turned an even deeper crimson by the reflections

of the rock on the water. |

This remote and rocky landscape is a haunt of large

numbers of birds of many diverse species, one that we frequently spotted all along the

river being the Egyptian vulture.The red waters of the river flow amidst white willows

with olive green foliage, and sometimes reeds and willows together. We saw anglers in the

welcome shade of the willows fishing for sheatfishes. Some were fishing with rods but

others with nets, despite this being illegal. The great number of fishermen was an

indicator of the teeming wildlife for which the river and its banks are a habitat.

Colourful dragonflies were plentiful all along the river. |

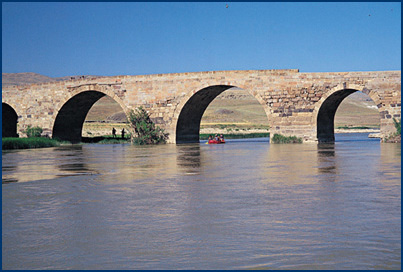

| There are many historic bridges over the Kızılırmak, and during our

journey we passed a halfruined bridge near Çukur, and the Çokgöz and Tekgöz bridges.

The latter was built in 1202 during the reign of Rükneddin Süleyman Şah, son of the

Seljuk ruler Sultan İzzeddin Kılıç Arslan II. Çokgöz is another Seljuk bridge which

is still in use. It has no less than fifteen arches, hence the name Çokgöz (Many

Arched). Past this bridge the river makes a sharp turn alongside cliffs, marking the start

of a stretch of spectacular beauty. Near Çukur, on a high rock rising from the river is

the awesome Zırha Castle, perched like an eaglsdm eyrie. Past Hırkaköy is a great

timber bridge nearly 150 metres in length and broad enough for cars to cross

which harmonises perfectly with the river, enhancing its beauty. The Kızılırmak

brings life to all the lands its passes through. Wherever the valley floor widens out even

a little, farmers take advantage of the fertile soil. Where the valley widens into plains

several kilometres broad there are villages. If not for the Kızılırmak this region

would be arid steppe land unsuited to agriculture. As we approached each village the sound

of motorised water pumps could be heard. The farmers raise water from the river to

irrigate their fields, relying mainly on water pumps, but where these are inadequate

constructing huge water wheels like the one which we saw at the village of Kuşcu.

The Kızılırmak reshapes the dry and harsh conditions of the central Turkish steppe,

creating an environment along its course on which many living things depend. This was

brought home to the five of us during our boat journey downriver.

|

- Kaynak:

- Skylife 08/2000,

By Ali Ihsan GÖKÇEN

|

|